The Innovation Lens …

See purpose as innovation’s prime mover …

Humans are energized by purpose — especially when it’s both personally compelling and larger than oneself.

For innovation practitioners, purpose fuels the human drive, imagination, and action of creating a brand new offering and putting it out into the world.

For example, for Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, social connection is a purpose that has magnetized him — something he believes matters in the world. In Zuckerberg’s words about Facebook:

For example, for Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, social connection is a purpose that has magnetized him — something he believes matters in the world. In Zuckerberg’s words about Facebook:

“But the biggest thing that thematically (the Social Network film) missed is the concept that you would have to want to do something – date someone or get into some final club – in order to be motivated to do something like this. It just like completely misses the actual motivation for what we’re doing, which is, we think it’s an awesome thing to do. … For me, computers were always just a way to build good stuff, not like an end in itself. … The thing that I really care about is making the world more open and connected. What that stands for is something that I have believed in for a really long time.”

See why, in the 21st century, society needs a lot of innovation.

From a lot of people fueled by their version of purpose

And empowered by innovation’s methods

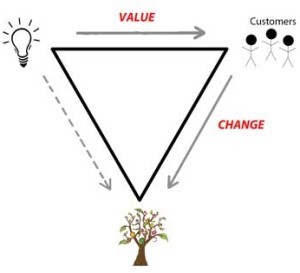

To generate change “by way of value.”

WIDE ANGLE LENS –> Responding to Value

A chain reaction of response to “value” provides innovation’s powerful and important force for change:

-

For practitioners — Practitioners respond to the value of compelling purpose, empowered as a concrete picture of possibility by way of innovation’s core methods. This response kicks off the chain reaction of value, as practitioners are motivated to create a particular type of new value for others in the form of an offering (e.g., a product or experience).

-

For customers — If enough customers find compelling value in the new offering and adopt it, this allows for positive change in the total value produced from existing resources (of any and all types — natural resources, technology, knowledge, human resources, etc.).

-

For society — The change of more value from the same resources allows for important societal-level benefits.

Societal-level benefits are the reason innovation matters.

Producing more value from the same resources makes the resources more fruitful.

In the 21st century, three key measures for resource fruitfulness are known as the “three P’s”:

- “Profit” — Advances in a nation’s total economy, measured by “Gross Domestic Product” (GDP), is associated with a higher overall standard of living. GDP captures the total amount of value produced by an economy from all sectors — commercial, social, and public — including both for-profit and non-profit organizations.

- “Planet” — Advances in the sustainable use of natural resources are fundamental to overall life on the planet, especially in light of a rapidly expanding population and finite natural resources. Offerings like recycling services must be received by customers as a positive — as an offering of compelling “value” — if the offerings are to realize the force of innovation’s chain reaction of value.

- “People” — Using resources more fruitfully for the benefit of advances in human “well-being,” or “flourishing,” is associated with “lives worth living” at any standard.

For example …

In the brief version of examples below and throughout the gallery of examples at this site,

Notice that innovation’s ultimate societal benefits rely on its chain reaction of forceful value — practitioners responding to compelling purpose, customers responding to a compelling new offering, and then the value to society of more fruitful use of resources:

- When Google’s founders (and subsequent employees) found compelling purpose in their discovery of the basis for a superior search engine and acted on it, with customers then finding new, greater value in the offering and adopting it, there was an advance in the amount of economic value (“Profit”) produced from existing resources such as the Internet and the founders’ computer science knowledge. Plus, customer engagement with Google’s search engine is likely associated with additional advances in “People” and “Planet.”

- A co-founder of FarmLogs software has merged his passion for computer science with his deep knowledge of farming and deep caring about farmers, based on growing up as a fifth-generation farmer. The FarmLogs offering draws on resources like GPS, weather statistics, the Internet of Things, and much more to permit farmers to use their land more fruitfully in crop production, for benefit not only to the farmer customers but to the overall economy (“Profit”). Plus, continuing development of the offering, including artificial intelligence enabled by the resource of data science, is to support the additional measures of “People” and “Planet,” by supporting enough food production for a rapidly growing global population.

- After the Ocean Cleanup’s founder was disturbed by the amount of plastic particles he encountered while diving in the sea, he experimented toward the compelling possibility of a new type of tool that would clean tiny plastic particles from ocean waters by making more fruitful use of ocean currents. This purpose and possibility magnetized not only the founder’s commitment and perseverance, but also the volunteer engagement of hundreds of scientists, engineers, and other specialists throughout the world. The resulting tool also magnetized its first customer — the nation of Japan. Continued customer adoption would make it possible for the Ocean Cleanup’s tool to advance sustainability of existing natural resources (“Planet”) and public health (“People”). Plus, the enterprise is designed to produce this new tool efficiently, to avoid or minimize negative economic effect (“Profit”).

- To the Khan Academy’s founder: “(W)hat really matters …is whether the world will have an empowered, productive, fulfilled population in the generations to come, one that fully taps into its potential and can meaningfully uphold the responsibilities of real democracy.” That purpose drove the creation of Khan Academy’s free online library of instructional videos. And now the more customers there are finding compelling value in the offering and the more that customers’ use of the offering facilitates successful thinking and learning (“People”), the more there is leveraging of the resources of the Internet and the philanthropic dollars that make the online offering free to everyone on the planet. From the year 2014 to 2015, when the number of registered users doubled (for a new total of some 20 million users), it’s likely that the offering allowed for a lot more learning from the ~same resources.

Zoom in just below for focus on each part of the chain reaction of value … beginning with focus on the practitioner.

ZOOM IN –> Value to Practitioners

Purpose provides motivation, and innovation’s methods provide empowerment.

-

With innovation’s methods, purpose assumes the form of a picture of possibility that’s both concrete and compelling.

-

That picture of possibility provides a map to action.

Why so powerful?

i. Personally compelling.

In the words of an Adobe Vice President of Creativity: “We innovate because we care.”

- In particular, when what’s personally compelling also is larger than oneself, it features the powerful value of “meaning.”

- A knowledge-based picture of possibility adds the value of a road map or bridge to action that supports the purpose. It makes the purpose accessible.

- Plus, when personal strengths support innovation’s medium of expression, there is added value to practitioners of “engagement.” The stronger the connection, the more there is potential for demanding work to be valued for the sake of the experience alone.

The positive force of purpose isn’t limited to founders. It can influence a large team of practitioners with widely varying strengths — complementary strengths — all channeled to the shared, compelling picture of possibility.

- When a broadening circle finds compelling value in the possibility, they “buy in.”

- They participate in bringing the possibility to life.

For example, an article about Facebook quoted a vice president “who was doing a master’s in artificial intelligence” and initially thought Facebook would be a waste of time:

“And the interview completely changed my mind. I saw the vision.

I came in, and I saw it on a whiteboard.”

Or to borrow a quote of Frederick Douglass, which seems applicable to innovators as well:

“Poets, prophets and reformers are all picture makers … the secret of their power and of their achievements.”

ii. Grounded in pertinent knowledge

The picture of possibility is based on innovation’s two types of hypotheses:

- “What could be” as new value that will be compelling to customers and is linked to innovation’s overarching function of more fruitful use of resources.For example: “If curbside pick-up makes home recycling convenient enough, many individual customers will find value in this opportunity to contribute to sustainability. And weekly curbside pickup, occurring on the same day as trash pick-up, will represent the right level of convenience to prompt broad participation.”

- “How” the new value can become an offering made accessible to customers, in order to catalyze change.One “how” hypothesis for the above example might be: “Initiating curbside pick-up simultaneously with neighboring towns can provide compelling value to a local business to provide the resource of pick up and processing, for an effect of natural resources going farther (“Planet”) with little or no increase in operational costs for waste disposal.”

Innovation’s hypotheses, like hypotheses for science, are formed by making new connections of pertinent knowledge:

- An idea may seem as though it comes from “nowhere,” but in fact it comes from making a new connection of existing knowledge.

- For example, the path of Google’s founders to their core innovation hypothesis of “what could be” as new value began with scientific hypotheses and experimentation. When they discovered patterns and traits of Internet links, they published scientific papers. But they also drew on this knowledge and more in forming their core innovation hypothesis: “We should use it for search.”

- Innovation’s hypotheses do not require scientific or technological knowledge. Many ideas are based on ordinary knowledge, as long as the knowledge is pertinent to innovation’s positive force of change by way of value.

Most important, for innovation, a “true” hypothesis is one that passes the customer test.

- Practitioners propose an offering of new value,

- But for innovation’s chain reaction, an offering’s value is in the eyes of customers.

A Map for Putting New Value Out into the World

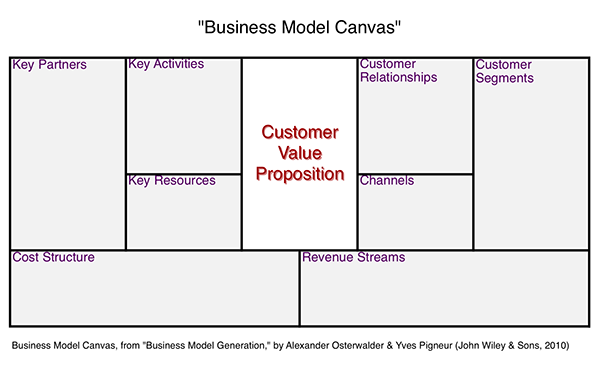

For any size or type of initiative, a framework such as a “business model canvas” (depicted just below) illustrates the types of “how” hypotheses that support a “what could be” hypothesis.

- Practitioners follow widely varying pathways to their “what” and “how” hypotheses, but most every path leads to this type of concrete picture of possibility, either explicitly or implicitly.

- Even though “business” is in the name of this tool, the framework is fundamentally about producing value from resources — which applies to most any type of organized effort to do this.

- The gallery of innovation examples at this site features “what” and “how” hypotheses behind widely varying types of offerings.

“How” hypotheses continue day to day:

- An offering’s overall map of hypotheses may change.

- Plus, the ideas never really end, as myriad day-to-day “how” hypotheses support the work of realizing the overall picture of possibility and sustaining it.

- These hypotheses are initiated by many different roles within an operation, incorporating different specialized knowledge and drawing on an array of personal strengths, all channeled to support the initiative’s ultimate new offering to end customers.

Innovation hypotheses as shared language.

- “What could be” and “how” hypotheses serve as practitioners’ shared language and the essential structure for collaboratively generating and sustaining a new offering — pertinent to the work of essentially everyone involved in an operation.

- The hypotheses represent the essential structure of innovation’s methods, which are essentially about “integrating and applying” knowledge toward new change-catalyzing value.

ZOOM IN –> Value to Customers — A compelling offering

Value is a positive force.

Even if a context is considered problematic, innovation’s force of value calls for a positive change catalyst.

- For example, for a public health problem of unhealthy eating, innovation’s force of “value” would call for imagining positive change catalysts such as healthy food worth eating for its taste alone.

- Similarly, for education, a classroom tool to generate greater student learning would call for teacher and student experiences of the tool that are positive enough to support engaged use of the tool and useful enough to produce the learning change.

The force of value is pertinent to most every human and social exchange.

New value as a force for change has been called pertinent to “all (human experience) except that which could be called existential, rather than social.”

- Some think of the possibilities for new offerings as supporting customers in their “jobs to be done” — from learning to mating to being entertained to staying healthy and so on.

- And some customers represent an organization (a business, school, city government, etc.) and its jobs to be done.

- The possibilities for new value extend across all dimensions of life and all economic sectors — social, public, and commercial.

Not all value is created equal

- All value is positive, but it’s not all equal.

- There are theories and/or frameworks that speak to what humans value most, to the human and social dynamics surrounding what is valued, etc.

- One theory, from the field of “Positive Psychology,” specifies five experiences of value that humans gravitate to most: positive emotions, engagement of personal strengths, positive relations, meaning (connecting to a purpose larger than the self), and certain types of achievement. Among this theory’s five categories, experiences like “meaning” (connection to purpose) are considered most valued, which seems like good news given society’s vast need for innovation.

- Overall, knowledge about human and social dynamics is one fundamentally pertinent strand for innovation’s hypotheses.

Pertinent to any scale

- Innovation’s possibilities for “change by way of value” also pertain to any scale (e.g., offering the value of more convenient recycling at scale as small as a single classroom, lunchroom, school, church, restaurant, etc.)

- The level of change at small scale may not be labeled “innovation,” but innovation’s essential forces and methods apply.

- This means there is a vast practice ground for budding innovation practitioners — for those who’d like to try their hand at catalyzing change that they care about by offering new “value” to others.

ZOOM IN –> Value to Society — The effect of more fruitful use of resources

Innovation’s ultimate societal effect can be the least visible.

Innovation’s ultimate societal effect can be the least visible.

- It’s ironic, since societal benefit is the reason that innovation matters so much that it has become a buzz word.

- At the same time, it’s the primacy of a personal and authentic pull to value — among many individual practitioners and individual customers — that allows for innovation’s high-leverage and lasting effects of change.

Exception of sustainability

- A key exception to low visibility probably is when sustainability of the natural environment is the societal benefit.

- For example, for offerings associated with renewable energy (solar panels, electric cars, etc.), the compelling value to many customers is the “meaning” of contributing to sustainability.

- As with all versions of value, meaning is in the eyes of the customer, and it’s positive, not an “ought” (although ease to an ought can represent a type of value). Meaning’s force comes from customers experiencing it authentically as “value.”

In the 21st Century …

Innovation’s change-by-way-of-value is considered essential for the progress of better lives for an expected global population of many more people.

There are also more knowledge-based resources than ever that can support compelling pictures of possibility for practitioners:

- Growing resources of knowledge, technologies, and access to information, all of which can be integrated and applied toward ideas for offerings of compelling new value.

- Better knowledge about innovation’s long-time practice of catalyzing change by way of value, including a treasure trove of models and tools to support hypotheses and action.

So what’s the key limiter?

- It’s innovation’s prime force of human connections to compelling purpose, empowered by innovation’s core methods.

- Those connections are the secret sauce not only for innovation’s large and urgently needed effects, they’re a secret sauce for engaging, compelling work.

- But finding this type of personalized connection to purpose usually isn’t easy.

- This web site aims to provide support for that exact challenge.

Your Type of Purpose

Use Innovation’s Lens as a Tool for Exploring and Discovering Your Types of Purpose

- Society’s needs and opportunities rely on individuals who care about all different types of things and are talented in all different types of ways.

- A societal challenge is to support individuals in exploring and discovering their own types of purpose, along with understanding how to catalyze positive change by harnessing innovation’s force of value for customers.

There are models and tools to support the practitioner “purpose” aspect of innovation’s methods, as with other aspects of these methods. For example:

- One model calls for considering large-scale societal changes that are underway or on the horizon and from this recognizing “symptoms” that signal opportunity for new value.

- For example, with the U.S. on the verge of a large wave of aging baby boomers, one symptom could be “gaps” in the existing array of services needed or desired by this demographic.

- Impact from climate change represents a whole different type of large-scale societal change, as does projections of the most influential technologies, including self-driving vehicles and other applications of artificial intelligence.

- Familiarity with the general landscape of projected societal changes, combined with innovation’s overall lens, can support a personal gauge of what captures your attention.

Use this site’s Gallery of Examples as one tool:

Try searching by what you genuinely think matters.

- Better access to clean water? To any water in areas of drought?

- More effective schooling experiences?

- Offerings for better access to music? To food? Better anything …

Also, use the examples and lens as perspective for seeing the everyday world — for noticing opportunities to create compelling new value from existing resources.

And use this site’s Blog for regular tips about discovering purpose and harnessing innovation’s positive power for catalyzing change.

Addendum:

Expanded comparison of innovation’s hypotheses versus those for science and invention —

Innovation |

Science |

Invention |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Advance societal yield from resources | Advance knowledge | Advance technical capability |

| Nature of Hypotheses | “What could be as new value to customers” & “How it could become an accessible offering and change catalyst.” |

“What is” | “What could be technically” |

| Medium of Expression | Offerings | Argument | Function |

| Domain of Change | Commercial & Social Production Systems | Disciplinary Fields of Knowledge | Disciplinary Fields of Knowledge |

| Pertinent Knowledge to be Connected | Multiple strands such as: industry/operations; customer; human & social dynamics; influential technologies; other. |

Disciplinary | Primarily Technical |

| Gatekeepers of Change | Customers | Experts in the Field | Varies |

| Agents of Change | Widely varying. | Typically masters of a field of knowledge | Typically masters of a technical field |